Inpro accused T-Mobile and RIM of infringement of its patent relating to electronic devices having user-operable input means such as a thumb wheel. (Pat. No. 6,523,079). After claim construction, the parties stipulated to summary judgment of noninfringement.

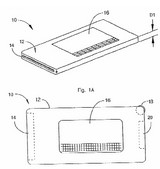

Inpro’s PDA design includes a thumbwheel controller with a host interface. The “PDA is designed to run independently by its own [CPU] until it is connected to a host computer. Upon connection to the host computer, the host CPU takes control and can access the memory and other functional units of the PDA.

Inpro appealed the construction of the term “host interface.” Interestingly, the specification only discussed the interface as a parallel bus, and actually disparages serial busses.

The appellate panel agreed the defendants that the term’s definition should be limited to parallel bus interfaces:

The description of a serial connection in the discussion of the expansion bus interface, and the lack of any such description in the discussion of the host interface, reinforce the interpretation of the host interface as requiring a parallel bus interface, for that is the only interface described for that purpose.

The real killer for the plaintiff was that the following line from the patent:

A very important feature of the PDA in an aspect of the present invention is a direct parallel bus interface . . .

Because RIM and T-Mobile use serial ports, they can’t infringe the patent, which is construed to require parallel ports.

Patent Drafting Commentary: This case reinforces the trend of intentional obscurity in patent drafting. Based on this case and others, patent drafters would do well to ensure that nothing in the patent document is “important,” “essential,” “required,” or the like. Those terms do help the patent readers better understand your preferred embodiment, but in court they will only limit your claim scope.

Additional views of Judge Newman: Judge Newman wrote the majority opinion, but added a separate addendum on her own. Judge Newman agreed that the court’s construction of “host interface” was dispositive in this case. However, she argued that the court should have construed all three disputed terms.

I believe we have the obligation to review the construction of the three appealed terms, for the interests of the parties and the public, as well as judicial economy, require final disposition of the issues of claim construction that were decided by the district court, and raised on appeal. This panel’s resolution of this infringement action based solely on the construction of “host interface” does not resolve, or render moot, the interpretation of the other disputed terms. . . .

We should review and decide all three of the disputed claim terms that are presented on this appeal, lest our silence leave a cloud of uncertainty on the patent, its scope, and its validity. Our obligation to the system of patent-based innovation requires no less.

Judge Newman’s view appears to be at odds with Judge Mayer’s recent dissent in Old Town Canoe.

It seems odd to me — in Philips v. AWH, even though baffles were taught in the spec as being useful only at other than 90 degrees, the decision allowed the interpretation of baffles in general. The judgment here seems to take the opposite view — since interface was only taught as / preferably taught as a parallel interface, the meaning of interface is restricted. I don’t get it. Comments?

Paul, regarding your comments about Wang v. AOL, please note the following:

The proposition that every variation and embodiment that falls within in the scope of a particular claim, should pursuant to § 112, be enabled by the spec, is just plain wrong and defies logic.

MPEP 2164.01(b) notes the following:

“As long as the specification discloses at least one method for making and using the claimed invention that bears a reasonable correlation to the entire scope of the claim, then the enablement requirement of 35 U.S.C. 112 is satisfied. In re Fisher, 427 F.2d 833, 839, 166 USPQ 18, 24 (CCPA 1970). Failure to disclose other methods by which the claimed invention may be made does not render a claim invalid under 35 U.S.C. 112. Spectra-Physics, Inc. v. Coherent, Inc., 827 F.2d 1524, 1533, 3 USPQ2d 1737, 1743 (Fed. Cir.), cert. denied, 484 U.S. 954 (1987).”

To be sure, the very essence of the doctrine of equivalents is to protect the inventor against pirates that substitute a certain claim element with a later developed technology. See, e.g., Pennwalt, 833 F.2d at 938, 4 USPQ2d at 1742 (“[T]he facts here do not involve later-developed computer technology which should be deemed within the scope of the claims to avoid the pirating of an invention.”)

As such, the bit-map protocol, (even regarding it as later-developed technology), was wrongly excluded from the claim scope in Wang. The inventors were not subject to the enablement requirement for every conceivable underlying protocol. The heart of that invention had nothing to do with underlying computer protocols, or computing platforms. Rather the crux of the invention simply related to certain novel “book-marking techniques”. Why would the particular protocol matter?

(Assume inventors of a particular software patent, relating to novel computer-implemented algorithms, confess during trial that they had sparse knowledge of the UNIX programming language, and could only implement their invention using C++. Would UNIX developers effectively receive a free ride on these novel patented algorithms? According to Judge Newman, the answer is, “yes”)

I stand with my previous post that Wang v. AOL is one of the most baseless CAFC decisions. I also find nothing intrinsically wrong in criticizing Judges for rendering ill-conceived decisions, especially when they are evidently biased under the spirit of curtailing “over-reaching inventors”.

I would just like to repeat for this debate the comments I made in relation to the following item (Patents are still “Very Important”), with a few addenda having regard to the present debate.

What are the drafting lessons which come from this case?

In my submission we should:

(1) Go through the features of the main independent claims, look for the corresponding features in the disclosed embodiments and make sure that alternatives are disclosed. If we do not disclose foreseeable alternatives we cannot rely on being given broad protection. That is the rule under 35 USC 112(6) but it is a good rule to apply generally. It is NOT just a question of legalese as suggested by Moshe but of having a full disclosure that will support the claim scope that the inventor desires and deserves to achieve.

(2) Be sparing about the features we identify as important. The Court may believe us.

(3) Don’t be afraid to identify what is truly important or preferred and why. Part of the public notice function (see Sage Products v Devon Industries for what the CAFC said on the topic of public notice) of a patent specification is to identify the features that make an important contribution to inventive merit and the reasons why they do so. If we do not identify such features in the specification and we get to an infringement trial, the court is apt to think that the feature we wish to rely on is not truly inventive but instead is “the afterthought of an astute trial lawyer” (see US v Adams).

There should be a balance in the drafting of patent specifications – inappropriate “patent profanity” is to be avoided but we should not fall into the trap of being merely “the bland leading the bland” (quoting J.K. Galbraith who died recently). There is a fashion for very bland specifications, especially in the electronics art and possibly a concentration on numbers instead of quality. When they come to be enforced, these bland specifications are likely to give the courts just as much trouble as their predecessors, but for different reasons, foreseeably including inventive step.

We have to be very careful with some of the case law propounded by the “patent profanity” proponents because what they say about object clauses or the word “preferred” often does not stand up when we examine the facts of the cases on which they rely. One of the decisions such proponents commonly cite is Gentry Gallery v Berkline, but if we study the decision we will find not only that there was no basis in the applicantion as filed for the broader claim language relied on at trial, but also that the inventor testified that the specification as filed accurately reflected his solution to the problem and that he did not think of trying for broader protection until he saw the design around.

Similarly in Alloc v ITC, which is another case commonly cited by proponents of “patent profanity”, the play which was written into the claim by the CAFC was in main independent claims of the application as filed via the PCT, was stated to be important during US prosecution and in an opposition to the corresponding European patent was considered to be the main inventive feature.

Similarly, if we look at the Wang Laboratories v America Online decision, we will see that there was much more to the decision than appears from Jonathan’s comment. The reason why the claim was limited to character-based technology and did nor cover not bit-mapped technology was that the disclosed technology would only work for character-based technology and had not been enabled for bit-mapped technology. The testimony showed that Wang had not been able to implement a bit-mapped protocol, and the CAFC held that the claims should not be construed to have a meaning or scope that would lead to their invalidity for failure to meet the enablement requirements of 35 USC 112. The reason for the narrow construction is not some wooden or slavish interpretation according to the wording of the specification but a legitimate desire to construe the claim according to the evidence before the court in a way that left it valid.

The various panels of the CAFC are in my submission (I am an Englishman and therefore by definition a non-expert) more conscientious and keen to give a just decision in the case before them than is sometimes credited by US commentators. It does not advance our understanding to stigmatize the CAFC as “politically motivated” or as motivated to strip inventors of their rights. What should be borne in mind is that courts by their very nature decide cases before them according to the evidence, and if we cannot immediately understand why a the CAFC handed down a decision the way they did, it is much better to try to figure out what was the evidence that lead them to their conclusion than to go blindly hollering that “this undermines the entire purpose of the patent system.”

Pauline Newman who was the judge in this case is one of the most respected members of the CAFC and renowned for her liberal attitude (I agree with Dan Fiegelson about this). If she says the claim term should be narrowly construed, then she probably has very good reasons for the view she has adopted based on the factual matrix before her.

Inpro and the Specification Firsters

Whatever a person sows, that also shall he reap.

Hence, the Federal Circuits claim construction decision today in Inpro v. T-Mobile.

Theres great discussion of the case at Patently-O, including comments from a number of folk highly critic…

DC,

The very issue in the case is whether the patentee still claimed “host interfaces” as a whole.

As for what patentees should be allowed to do, I agree they should be allowed to say that A is better than B and C while still claiming B and C. After all, that’s simply a best mode distinction. (A is my best mode, B and C work too.)

Isn’t what happened here more like “A is good; indeed, it’s very important to my invention. And B, which is in the prior art, is really crummy.” If that is what happened here, why isn’t the natural interpretation of the claim term “A, not B”?

Dan’s comment about Judge Newman being the author of today’s decision brings to mind the Wang v. AOL case.

In that 1999 decision, Judge Newman wrote one of the CAFC’s most baseless decisions. The Wang case was one of the first in the trend-setting precedents for importing limitations from the spec.

Construing the term “frame”, Judge Newman noted that the term must mean “character based” frames and cannot cover “bit map” frames, because “the only embodiment described in the ‘669 patent specification is the character-based protocol”.

Indeed, nothing in the ‘669 patent would give the impression that the “character-based” protocol is “important” to the invention. Rather, the reason that feature was imported into the claims, is because the “only” embodiment of the spec included that feature.

I distinctly remember the Wang decision, because I recall that it is full anomalies.

1. It wrongly limits the claims to the single embodiment of the spec.

2. It wrongly requires the spec to enable every embodiment covered by the claims.

3. It disregards (as in today’s case) the claim differentiation doctrine.

True, the applicant disparaged the use of serial interfaces and said they were not as good as parallel interfaces. However, the patentee still claimed “host interfaces” as a whole.

Patent applications should be allowed to say that A is better than B and C — while still claiming B and C.

While I agree with Moshe’s comments apropos the difficulties imposed by courts which import statements from the spec into the claims, I don’t think this particular decision is deserving of those comments. In another statement in this decision, not reported in the Patently-O summary, the CAFC noted that the spec explicitly disparages serial ports. There’s nothing new about jurisprudence saying that if you disparage a particular prior art configuration for claim element X, you’ve excluded that configuration from the definition of claim element X. I also think that if you check historically, Judge Newman, the author of today’s decision, is one of the leaders against the trend to import limitations from the spec into the claims.

Reading all these post-Philips Federal Circuit opinions, I keep on wondering… What if the patentee had explicitly stated during prosecution that the claim term should be construed broadly? Suppose the patentee in Inpro had expressly stated during prosecution that the definition of “host interface” is not limited to a parallel bus. What happens then? Obviously, the CAFC cannot forcibly interpret “host interface” against express definitions of the patentee. But then, does the claim become invalidated for failing the “written description requirement”? Does the mere statement that “a very important feature of the PDA in an aspect of the present invention”, require that every single claim include that important feature? Based on CAFC precedents, the answer would be “yes”. Everything you say in the spec or during prosecution that touts a certain feature of “the invention” necessarily mandates each and every claim to include that feature.

Unfortunately, the current CAFC jurisprudence couldn’t have been more twisted and crooked. Here’s why.

Assume the “written description requirement” is separate from “enablement”. What constitutes an adequate “written description”? Unlike the functions of “claims” and “enablement”, which are handily explained in the statute, the term “written description” is just an obscure two-word function. Unfortunately, the CAFC has taken to interpret this term very liberally, without precedent.

Nothing in the statute conveys the notion that the “written description” serves the purpose of setting boundaries and scope of the invention. To the contrary. The statute makes it clear that the claims define “what the patentee regards as his invention”, and nothing else. Further, the statue makes it clear that the patentee “regards as his invention” may change over time. It is an unequivocal axiom of patent law, that claims are amendable. You can file a patent application claiming ABCDE (i.e. regarding your invention as ABCDE), and then drop E, and just claim ABCD (i.e. changing your mind by deciding to regard your invention as just ABCD). That’s what “claim amendments” are all about. It’s the very purpose of “broadening reissues”? The law is just crystal clear. While you may narrowly “regard” your invention upon filing the application, you may subsequently, at later date, broaden what you “regard” as you invention.

Regrettably, the politically-motivated CAFC, has effectively stripped patentees from their rights to claim, to reclaim, and again to reclaim (i.e. regard your invention, re-regard your invention, and again re-regard your invention).

Based on current CAFC jurisprudence whatever you state in the specification would work against you. Should you state that the invention includes element X, then every claim must include element X. But then, should you state that the invention “may” include element X, then element X cannot necessarily be considered as an integral part of your invention. You cannot then overcome prior art by reconciling during prosecution that “the invention” does in fact require element X (i.e. you failed the WDR, by stating that the invention “may” include element X).

This Undermines the ENTIRE purpose of the Patent System

——

This “importing” of limitations from the examples of the spec into the claims forces us patent drafters to insert tedious legalese throughout our specs to make sure our clients don’t get screwed out of the protection they deserve (i.e. “in some embodiments, X, in some embodiments Y” and TONS of other worthless, useless phrases). We can NEVER write “preferably X” even if this would be useful information for someone trying to understand the invention.

We cannot write “an object of this invention” (like people wrote for decades) and disclose “advantages” of the invention, because some IDIOT (not the examiner, who give the claims the broadest interpretation) will “import” these limitations into the spec. PATENT LITIGATION IS SO UNPREDICTABLE !!!

Bad Result A – the public gets cheated out of a clear disclosure !!!

As a PhD engineer (now a patent agent), I can tell you that THIS (and triple damages)is why very few scientists and engineers read patent disclosures.

Bad Result B – the poor client needs to pay more for the services of patent agents and attorneys who need to spend time “restraining” the inventor’s disclosure document when writing a spec. Also (see below), it causes us to spend more hours writing a spec that is good for the USA AND for Europe.

Bad Result C – when trying to get protection in Europe, we have another problem – there the Examiners actually want us to commit to saying what has been invented (WHAT A CONCEPT !!!!) (often, for the right to claim during prosecution material that is initially unclaimed). Now we are stuck between a rock and a hard place – this problem DOES get solved (my recommendation is to write a Kayton-like “low-profile” spec and to claim EVERYTHING in the PCT so the Europeans won’t deny the right to claim something during prosecution). BUT this, of course, takes more time and raises the costs for the client.

Comments are closed.