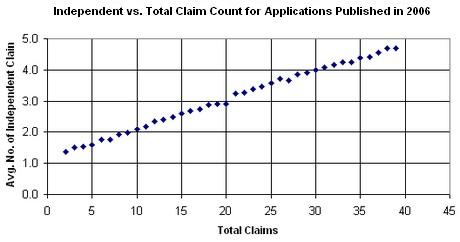

Part II of my new series on evidence based prosecution focuses simply on a descriptive feature of the patent application. How many independent claims should you file? Although we don’t answer that question here, we can answer the question of how many are usually filed. Using data collected from patent applications published thus-far in 2006, I constructed the chart above comparing the average number of independent claims in a patent application to the total number of claims in the patent.

To continue reading, become a Patently-O member. Already a member? Simply log in to access the full post.