By Prof. Paul M. Janicke, HIPLA Professor of Law, University of Houston Law Center< ?xml:namespace prefix ="" o ns ="" "urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:office" />

In the 1980s patent practitioners were being pressed by clients to keep costs down. At the same time they were seemingly presumed by courts to understand right away any prior-art reference that made its way into their offices, and how that reference might relate to patent applications they were writing or prosecuting. They were rather upset with the drift of the law on inequitable conduct. It seemed the courts were allowing something short of intentional deception to make out that defense and to ruin a client’s otherwise solid case for validity and infringement. Language like “gross negligence” had crept into some of the appellate decisions. With enough time and funding by the challenger, many non-cited things in a patent practitioner’s possession could be made years later to look important to patent prosecution, and explanations for non-citation always seemed at that late date a little lame. All the challenger needed to do is find one of those things and persuade the judge to label the non-citation as gross negligence.

However, shortly after Kingsdown a number of other cases rightly pointed out that deceivers seldom come forth and say they acted with intent to deceive. “Such intent usually can only be found as a matter of inference from circumstantial evidence.”[3] Through the 1990s the Federal Circuit appreciated the continuing need to make an actual finding that a particular person acted to mislead the PTO in a particular way. It told us “a finding of intent to deceive the PTO is necessary to sustain a charge of inequitable conduct.”[4] In a withholding-type accusation, reaching that conclusion of course requires a subsidiary finding that the person appreciated the significance of the withheld item. Without that appreciation, he can hardly be trying to deceive the examiner about the item.

In the last three years Federal Circuit panels have slipped back into “should have known” language to arrive at the conclusion of intent to deceive or mislead the PTO.[5] That is the language of simple negligence. Even more troublesome, they seem to have reached the “should have” finding by reference to the importance (materiality) of the item to the prosecution proceeding, the logic of which is somewhat elusive. In 2008 a number of cases have now explained how all this is consistent with Kingsdown. Negligence alone might not be enough, but when material information is found in the hands of persons connected to patent prosecution, they need to provide a “credible explanation” or suffer a finding of bad intent.[6]

The trouble with this approach is that it allows even simple negligence (“should have known”) to shift the burden of persuasion on intent to the patent owner. This shift will happen in just about every case, because the finding of materiality in a combative courtroom setting will nearly always generate the “should have known” prong, shifting the entire burden of credibly showing benign intent onto the patentee. In the dynamic of actual patent litigation years after the events in question, that burden is indeed a fearsome one. In life, consider how often we ask ourselves when bad situations arise: “Why did I do that? Why didn’t I see the connection?” Credible-sounding explanations are not that easy to come by, even when we know we are innocent. Explanations on the ground of human fallibility feel hollow, and this is especially so in the majestic setting of a court proceeding. The patent bar and their clients have gone out of the frying pan and into the fire.

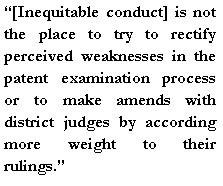

Some rays of hope have appeared for rectifying the situation. Judge Newman dissented in Nilssen, the small-entity status case.[7] And Judge Rader has seen the problem in what I regard as its proper light. In May of this year two panel judges sitting with him upheld a district court’s finding of inequitable conduct in a withholding-of-information case. The two were unwilling to reverse the lower court’s conclusion that the explanation given for non-citation was not credible.[8] Dissenting, Judge Rader said: “[M]y reading of our case law restricts a finding of inequitable conduct to only the most extreme cases of fraud and deception. . . Although designed to facilitate USPTO examination, inequitable conduct has taken on a new life as a litigation tactic. The allegation of inequitable conduct opens new avenues of discovery; impugns the integrity of patentee, its counsel, and the patent itself; excludes the prosecuting attorney from trial participation (other than as a witness); and even offers the trial court a way to dispose of a case without the rigors of claim construction and other complex patent doctrines.”[9] Amen to that. This is not the place to try to rectify perceived weaknesses in the patent examination process or to make amends with district judges by according more weight to their rulings. Worthy and important goals those may well be, but shifting burdens on inequitable conduct is not the way.

Inequitable conduct burdens have in the past rightly been placed on the challenger. Establishing this defense has required a finding not about what a person should have known, but that the person involved actually did appreciate of the significance of the information to the prosecution process. Now the burden on the intent prong has de facto shifted. Hopefully it will return to where it was. I have always thought the relative importance of the item as seen years later has little to do with finding an intent to mislead. Most of the time it is just as easy in life to fail to connect important dots as unimportant ones.

[1] 863 F.2d 867 (Fed.Cir. 1988), cert. denied, 490 < ?xml:namespace prefix ="" st1 ns ="" "urn:schemas-microsoft-com:office:smarttags" />

[2]

[3] Hewlett-Packard v. Bausch & Lomb, 882 F.2d 1556, 1562 (Fed. Cir. 1989).

[4] RCA Corp. v. Data General Corp., 887 F.2d 1056, 1065 (Fed. Cir. 1989), emphasis in original.

[5] See

[6] See Nilssen v. Osram Sylvania, Inc., 528 F.3d 1352, 1359-60 (Fed. Cir. 2008) (inequitable conduct finding upheld based on wrongful claiming of small entity status, where explanation testimony was not credible); Pfizer Inc. v. Teva Pharms.

[7] Supra, note 6, 528 F.3d at 1362-65.

[8] Aventis Pharma S.A. v. Amphastar Pharm. Inc., 525 F.3d 1334, 1349 (Fed. Cir. 2008).

[9]

“I believe it is not appropriate to generalize and state that those involved in the prosecution of patent applications are somehow unable to ‘wrestle with arguments on their actual merits.'”

Mr. Slonecker,

I didn’t intend to generalize quite that much. I did intend to suggest that those who “argue” by reference to an opponent’s credentials are in fact relying on an approach that has been recognized as invalid since at least Aristotle’s time. You can impeach a fact witness by attacking his credibility, but it is invalid to apply that approach to a logical argument. If there’s a mistake in the logic, point it out. If there’s a mistake in a factual pre-requisite to the argument, point that out. But it’s laziness, ignorance, or sophistry (or some of each) to rely on ad hominem arguments.

You makes some good points, Mark.

It’s interesting to see the arguments here on inequitable conduct (IC) reverting again and again to good/bad patent, 102/103 issues. If the uncited art is really as good as is alleged by the defendent so as to invalidate a patent on prior art grounds, then IC really becomes pointless. Simply invalidate it on prior art grounds using the newly cited reference, instead of trying to argue materiality and ‘implied’ intent to deceive. Using IC seems to be the lazy approach to litigation to avoid having to argue the merits of the patent.

“Once again, there is this assumption by at least Judges Radar…”

Judge Radar? That sounds like a new nemesis for Batman.

Seriously: Paragraphing. Pa-ra-gra-phing. Thank you.

I had absolutely no idea that for the past few decades I have committed so much intentional/negligent inequitable conduct.

Groveboy1 from your posting, my guess is that you are not registered to practice before the Patent Office. For example, you refer to inventors signing “certifications” and you refer to an obligation to conduct full and exhaustive prior art searches.

Once again, there is this assumption by at least Judges Radar and Newman that the corporate titans who benefit from the patent system and the patent prosecutors beholden to them almost always try in good faith to meet their disclosure obligations and, therefore, the doctrine of inequitable conduct is merely a tool used by clever infringers to wrongfully create a false portrait of wrongdoing.This assumption is wrong. Sadly, in my more than thirty years of experience as a patent litigator on both sides of the aisle (patentees and accused infringers), I have come to conclude that inequitable conduct is indeed a plague–there is so much undetected inequitable conduct by so many unscrupulous patent prosecutors and inventors (and the corporate masters they serve) as to bring into question the integrity of the entire patent system. Inventors in most companies are allowed to abdicate their disclosure duties by relying on in-house patent prosecutors to handle the entire patent process–most inventors sign certifications in support of patent applications without even bothering to read the patent specifications (which itself should be deemed inequitable conduct). Patent prosecutors (particularly those who serve in house) have enormous incentives to cut corners (and costs) by omitting pesky inconsistent test data, and avoiding disclosure of inconvenient prior art (believing that even if it is material, it eventually will be distingushed and overcome, so why bother disclosing it) so as to reduce the costs of patent prosecution and assure success. Sadly, I have reluctantly concluded that a large percentage of patent prosectors fail to take their disclosure obligations as seriously as they should, fail to conduct full and exhaustive prior art searches, fail to make inquiries of their clients regarding inconsistent test results, fail to communicate with inventors concerning the accuracy of statements in the patent specification (often relying exclusively on communications with in-house counsel,department heads or administrators, fail to ask the inventors and clients whether they know about inconsistent test results, and fail to apprise examiners of co-pending patent applications concurrently prosecuted by their clients before different examiners that implicate many of the same issues. Smoking gun evidence of such misconduct is almost impossible to find because patent prosecutors can hide behind the attorney-client privilege. That is why in a series of thoughtful opinions Federal Circuit panels have wisely held that District Courts may infer intent from evidence sufficient to establish recklesness, gross negligence or negligence in circumstances in which the patentee is unable to provide an innocent explanation for the misconduct. Judges Radar and Newman (and perhaps some others) fail to recognize that the true plague is not the doctrine of inequitable conduct itself, but the fact that inequitable conduct is so rampant in a system wherein the corporate titans who benefit from the patent system fail to provide sufficient resources (i.e., fees and expenses) to permit patent prosecutors to comply fully with their disclosure obligations, resulting in the need for patent prosecutors to improperly “cut corners” in order to make their practices profitable. If anything, we need to make it easier, not harder, to prove inequitable conduct, so as to provide incentives for those who benefit from the patent system to provide sufficient resources to permit patent prosecutors to comply more fully and faithfully with their disclosure obligations. Further, we should hardly shed tears when patents are lost due to the gross negligence or negligence of patent prosecutions, who fail to provide good faith explanations for their conduct. I fail to understand why there is so much sympathy in the academic world for those who, motivated by corporate greed, repeatedly cut corners or otherwise fail to satisfy disclosure obligations merely because there is insufficient money in the patent prosecution budget to comply with disclosure obligations. Rather than raise the bar for proving inequitable conduct, we should lower it–negligent violation of disclosure obligations by patent prosecutors should be sufficient to render a patent unenforceable.

“French philosopher quoted with approval on US IP Blog…”

I’m reminded of Carl Spackler, who, while pursuing a pesky golf course with explosives in the movie “Caddyshack”, said: “In the immortal words of Jean-Paul Sartre: ‘Au revoir, gopher.'”

>>>In the words of Albert Camus, “You cannot acquire experience by making experiments. You cannot create experience. You must undergo it.”

French philosopher quoted with approval on US IP Blog – stop the presses!

Actually, I don’t really see the point of this quote – experiments are about acquiring knowledge through experience – there’s a clue in the fact that both words have the same root: present participle of “experiri”, “to try”. Absurd! (an attempt at a little Camusian humour there…)

The rantings often seem on this board bring to my own mind WB Yeats (Irish): “The best lack all conviction, while the worst/ Are filled with a passionate intensity”.

What if an inventor does not intentionally deceive the PTO, but knowingly disregards the obligation to disclose material prior art to the PTO? i.e., with a strict requirement of intentional deceit to prove inequitable conduct, isn’t an inventor better off signing an oath with no understanding of his/her undertaking, or if there is an understanding of the duty to disclose, simply disregarding it. For example, the inventor may fail to make any any consideration of what art might be of interest to the Examiner (they often have more pressing things to do than care about the quality of their patent) – in this case, the obligation to disclose material prior art would have been violated, but without any intent to deceive (no IC under a requirement of intentional deceit).

I think these cases (recognizing the “higher” materiality may allow for a gross negligence standard) address this. If your patent is predicated on a promise to the USPTO, then that promise should mean something.

Mr.BigGuy

“Indeed it is, because it is important to discount opinions of those who are not exactly like us, since we’re unable to wrestle with arguments on their actual merits.”

Please note I expressed no opinion about the views of others, and limited by notation to “useful”, and certainly not “important”.

A point was earlier made by an individual identified as GP that certain persons seemed inclined to agree with Mr. Janicke, even though he is now in academia, but not inclined to agree with others in academia…the basis apparently being that such others reside within an “ivory tower”. Another person responded by reference to Mr. Janicke’s law school profile, whereupon GP countered that Mr. Lelmley possesses similar credentials…and yet Mr. Lemley is not accorded the deferrence as Mr. Janicke.

Perhaps, in the matter of “inequitable conduct”, this may be the case in part because of Mr. Janicke’s longstanding experience in all facets of patent law, certainly including patent application prosecution. Inequitable conduct is, after all, associated with actions of applicants and their counsel during patent application prosecution. Of course, Mr. Lemley does not have the benefit of such experience, and it is this limitation in his experience that motivates some to comment as they do. It is, of course, unfair that GP chose to introduce Mr. Lemley’s name into the conversation. There are many in academia who are similarly situated.

While there are doubtless some exceptions, I believe it is not appropriate to generalize and state that those involved in the prosecution of patent applications are somehow unable to “wrestle with arguments on their actual merits”.

In the words of Albert Camus, “You cannot acquire experience by making experiments. You cannot create experience. You must undergo it.” I believe there is much merit in his quote.

“It is useful to note, however, that Mr. Janicke has been admitted to practice, and has practiced, before the USPTO Bar since 1969. Mr. Lemley is not admitted.”

Indeed it is, because it is important to discount opinions of those who are not exactly like us, since we’re unable to wrestle with arguments on their actual merits.

Re: Posted by: GP | Aug 08, 2008 at 05:14 PM

I express no opinion concerning the views of Messrs. Janicke and Lemley.

It is useful to note, however, that Mr. Janicke has been admitted to practice, and has practiced, before the USPTO Bar since 1969. Mr. Lemley is not admitted.

“IBM’s patent 7,407,089”

On its face, I have trouble with claim 1 passing § 101 muster as patentable subject matter. A “method for determining” is a euphemism for saying “formula,” i.e., “a determining method.” Moreover, the element “retrieving … information” is not useful unless such information is placed into use.

But having the initial burden on the Office in this application should have been an easy first OA rejection for the examiner

“Heavy burden? After KSR all it seems they need to do is perform a word search, slap a few references together, and call it a day. The appeal board will then uphold their rejection… or reverse it but enter a new grounds of rejection.”

Actually, I was not attempting to argue that the burden is heavy (although there are ironic situation where things are so bleeding obvious that nobody writes them down). My point is that there are cases, and this is a good example, where putting the initial burden on the office to show non-obviousness is going to look ridiculous to just about everyone. This perception of ridiculousness may well drive changes to the law.

For example, does anyone really doubt that Lemelson pretty much single-handedly provided the impetus to do away with terms running 17 years from issuance?

“The fact that such claims are routinely presented to the office, and prosecuted (too often successfully) by heavy reliance on the initial burden the office has in making out a case for non-obviousness”

Heavy burden? After KSR all it seems they need to do is perform a word search, slap a few references together, and call it a day. The appeal board will then uphold their rejection… or reverse it but enter a new grounds of rejection.

“IBM’s patent 7,407,089”

The priority of this “paper or plastic” invention is to Canada. (08-24-2005). Thanks Canada. Per the Notice of Allowance, the examiner, “Paultep Savusdiphol”, allowed this case on 04-16-2008 because of the lack of motivation to combine the references. This was long after KSR came out.

———————–

“IBM’s patent 7,407,089” reads: comprising the steps of:

(1) identifying the customer using a customer identifier; and

(2)retrieving available container packaging preference information for the purchased items using the customer identifier for the identified customer.

“The good professor has 20 years of patent litigation experience. Nobody could reasonably dismiss him out of hand as a non-practicing academic when he writes on this particular topic.”

The same can be said of Mark Lemley and other academics for example, and that didn’t stop people on this blog from dismissing them.

“Jim H — there is no distinction between any of those claimed methods with respect to their obviousness in view of the prior art.”

Indeed. The claim is obvious on its face, and would remain so unless and until some substantive technical feature of said “automation” is recited in the claim to give an Examiner something nontrivial to search for. I would be in favor of setting up a process to kick this kind of claim back to Applicant with a “where’s the beef” rejection that need not cite any prior art. Pulling an E6k, 112 could even be turned to this purpose — as it is self-evident that nothing inventive is in the claim, it cannot comply with 112.

The fact that such claims are routinely presented to the office, and prosecuted (too often successfully) by heavy reliance on the initial burden the office has in making out a case for non-obviousness, is the main reason that the initial burden may well shift to Applicant once Congress finally acts.

The good professor has 20 years of patent litigation experience. Nobody could reasonably dismiss him out of hand as a non-practicing academic when he writes on this particular topic.

link to law.uh.edu

It’s funny how the patent prosecutors posting comments on this blog, who usually howl “oh he is an ivory tower Academic who has never practiced and therefore knows nothing” are suddenly commending a law school professor’s viewpoint.

Jim H — there is no distinction between any of those claimed methods with respect to their obviousness in view of the prior art.

“Adding a computer/bar code to an old method is obvious absent unexpected results, teaching away in the art. You don’t have any of that here and you never will. This is classic business method garbage.”

Examiner Malcolm,

That you for removing your 102 rejection.

Next, there is nothing being “added” to an old method. Rather, there is a substitution or replacement of the human step with an automated step.

You believe replacing a human process with an automated process in unpatentable, correct?

You may resume puking if you are so inclined…but before you do…

if I have any objection to the claim, it would be the method of “determining.” I would definitely not have a problem if it were changed to the read the following:

1. A method of [generating a signal representative of] a customer’s packaging preference in a conventional point-of-sale retail location, wherein the point-of-sale retail location includes a person who performs the packaging of items purchased in the point-of-sale retail location for the customer, comprising the steps of:

identifying the customer using a customer identifier;

retrieving available container packaging preference information for the purchased items using the customer identifier for the identified customer[; and

generating a signal representative of a customer’s packaging preference, where such signal is used for the display of the customer’s packaging preference to the person who performs the packaging of items.]

Would this be acceptable (I am trying to distinguish where you draw the lines of software as “business methods” and that used to increase the efficiency of a mechanical process that would make Frederick Taylor proud)?

If you have any puke remaining, please resume; if not, please begin dry heaving….

I prefer that my bags be carried to my vehicle. I prefer that the cashier keeps the pennies. I prefer that the ice cream gets put in a plastic bag. I prefer that the tomatoes be put on top of the other produce. Can I put that info on “my card” too? I should file a patent on “communicating” that stuff. It’s at least as non-obvious as this pile of doodoo.

“This response removes the basis of your anticipation and obviousness rejections.”

Adding a computer/bar code to an old method is obvious absent unexpected results, teaching away in the art. You don’t have any of that here and you never will. This is classic business method garbage.

“This claim is anticipated or obvious in view of the hundreds of times that a clerk at a local store recognized me by my face and put my food in a paper bag because he knows that’s what I prefer.”

Examiner Malcolm,

Temporarily suspend your puking. I have amended the claim in response to your rejection:

1. A method of determining a customer’s packaging preference in a conventional point-of-sale retail location, wherein the point-of-sale retail location includes a person who performs the packaging of items purchased in the point-of-sale retail location for the customer, comprising the steps of: identifying the customer using a customer [identifying bar code]; and retrieving available container packaging preference information for the purchased items using the customer [identifying bar code].

This response removes the basis of your anticipation and obviousness rejections.

What’s you new basis for rejection?

Resume puking….

Re 7,407,089, I just love claim 4

3. The method of claim 1, further comprising the step of communicating the retrieved container packaging preference information to the person who performs the packaging in the point-of-sale retail location.

4. The method of claim 3, wherein the communicating step is performed graphically.

Does that cover the cashier waving either a plastic or a paper bag at the “performs the packaging”?

“I don’t doubt the invalidity of some (or even large numbers of) patents. I don’t doubt as well that deep-pocket infringers get away with stealing the work of others by conning lazy (or ignorant) judges with dubious arguments about IC.”

It’d be nice if you could provide an unambiguous example of a valid patent being tanked by an improper IC finding (and upheld by the CAFC).

Garbage patents, of course, are legion. We need not run through the list again.

BTW, I came across an earlier thread about the presumption of validity that might interest folks:

link to patentlyo.com

The consensus sems to be that because the Supremes never acquiesced in the CAFC’s clear and convincing gloss, then the Supremes could abrogate it judicially.

There were also interesting discussions about whether the clear and convincing gloss is really meaningful or not. I have to plead ignorance on that question.

“You appear to be a pro-patent peddler of pablum.”

Ad hominem. –adjective 1. appealing to one’s prejudices, emotions, or special interests rather than to one’s intellect or reason.

2. attacking an opponent’s character rather than answering his argument.

(from dictionary.reference.com)

I don’t doubt the invalidity of some (or even large numbers of) patents. I don’t doubt as well that deep-pocket infringers get away with stealing the work of others by conning lazy (or ignorant) judges with dubious arguments about IC. There’s no necessary contradiction between the two statements.

“If this is so obvious, then why isn’t it currently being practiced?”

It was being practiced for years before this patent was ever filed. The patent is a joke. The PTO is a joke. I puked my breakfast all over myself looking at this. Shame on everyone involved with this pile of garbage:

Here’s claim 1

1. A method of determining a customer’s packaging preference in a conventional point-of-sale retail location, wherein the point-of-sale retail location includes a person who performs the packaging of items purchased in the point-of-sale retail location for the customer, comprising the steps of: identifying the customer using a customer identifier; and retrieving available container packaging preference information for the purchased items using the customer identifier for the identified customer.

This claim is anticipated or obvious in view of the hundreds of times that a clerk at a local store recognized me by my face and put my food in a paper bag because he knows that’s what I prefer.

End of analysis.

[resumes puking]

“You appear to presume that patents are invalid.”

You appear to be a pro-patent peddler of pablum.

Many patents are invalid. It is a fun, rewarding and occasionally profitable public service to point out which ones are invalid and why.

re BM’s patent 7,407,089

On the face of the claims, the patent may seem invalid on 103 under KSR.

Question: If it so obvious, why is it that everytime a buy an item that needs to be bagged the clerk asks me “paper or plastic” where there is a choice? The use of scanners and the choice between “paper or plastic” have been around since at least the 1980s, and it is likely that savings cards (storing personal information for the purpose of data mining) have been around just as long.

If this is so obvious, then why isn’t it currently being practiced? It makes the process more efficient (perhaps at a loss of the human element of voice contact), and I would suspect supermarkets would jump at the chance of increasing productivity (especially if the purchaser is distracted from the check-out process, e.g., kids, cell phone, getting that last minute item, etc…).

I realize that the actual reduction to practice of this invention is very easy (updating a few lines of code to receive shopper information, receive shopper information input, and generate an output signal), but didn’t the inventor have to conceive and reduce to practice?

It may seem obvious to us now that it is invented, but others have had at least twenty years to develop the invention.

I am not sure that this is a clear-cut case of obviousness under KSR.

“Smashmouth, you are not falling into the pointy-headed trap of presuming it to be invalid? Are you?”

Presumptions are rebuttable. BTW, I would guess it might be a good idea, as some pointy-heads have proposed, to relax the burden from clear and convincing to preponderance of the evidence. The problem is that conventional canons of statutory construction preclude the CAFC from simply decreeing that henceforth 35 USC 282 shall be interpreted to require only preponderance of the evidence. As I understand it, the rule is that long-standing statutory interpretations acquiesced in by subsequent legislative inaction amount to implied legislative concurrence. In other words, the fact that CAFC (and I’m pretty sure its predecessor court CCPA) attached the clear and convincing gloss to 35 USC 282 without Congressional action for decades means it probably requires enactment of a statutory change to relax the burden.

“Lowly let’s take IBM’s patent 7,407,089. That’s the one about dispensing a paper bag or a plastic bag, depending on which one the checkout customer designates. It’s an IBM JOKE on all of us, isn’t it???? No problems on 102 or 3 or 12. Despite “reject, reject, reject”, it issued this week. Strikes me as a thoroughgoing bad one, which the PTO let through only because of the difficulty of finding a prior printed publication. I think the excellent EPO subject matter classification system would not have helped either. How often does this happen?”

If it’s bad, it should be invalidated during litigation, not because the attorney didn’t cite art not material to patentability that was cited by the very same examiner in a related case.

Do some of you have any real exposure to litigation? IC is raised all the time and it is usually raised in scenarios where where was a simple clerical error (ie. not citing art cited by China in the third continuation of a related case).

MaxDrei:

(1) Picking these cat-exerciser patents out and waving them around isn’t really fair, and we both know it. The PTO is a government entity that processes half a million complex documents a year. Of course some are completely screwed up.

(2) you are assuming there’s not 102/103 art. A quick perusal of PAIR shows that the 103 rejection was overcome with a TSM argument. Even the notice of allowance notes that everything was taught except applying the customer preference info to “container packaging preferences” (i.e. “paper or plastic?”) and without the applicants teaching, there is no motivation to combine.

So, no, under KSR this patent should not have issued and there is good art right in the file.

Bad patent? yes, on 103 grounds under KSR.

Surprising? No.

Smashmouth, you are not falling into the pointy-headed trap of presuming it to be invalid? Are you?

“IBM’s patent 7,407,089”

I had to read this to believe it. What about Sections 102 and 103??

Thank you Oh Dear for making me better informed. You make my point. The UK doesn’t have IDS. You say the UK still has “all” its common law but, tell me, what happened to equitable discretion, on amendment of EP(UK)’s?

“When you consider the windfall that results, compared to the remote chance of sanctions/imposition of attorney’s fees, I would expect that every patentee would sue or threaten to sue as many entities as it could afford to, regardless of how the patent was obtained.

Welcome to capitalism.”

You appear to presume that patents are invalid. I think 35 USC 282 says otherwise. I’ll acknowledge that some pointy-head academic types (e.g., Lemley, Rai) have attacked the presumption of validity, but at least as far as I’m aware, none of them would go so far as to presume invalidity.

Lowly let’s take IBM’s patent 7,407,089. That’s the one about dispensing a paper bag or a plastic bag, depending on which one the checkout customer designates. It’s an IBM JOKE on all of us, isn’t it???? No problems on 102 or 3 or 12. Despite “reject, reject, reject”, it issued this week. Strikes me as a thoroughgoing bad one, which the PTO let through only because of the difficulty of finding a prior printed publication. I think the excellent EPO subject matter classification system would not have helped either. How often does this happen?

Max Drei – you are horribly misinformed. England might “belong to Europe”, but it still has pounds sterling instead of the euro and it still has all its English common law and statutory law. It did not go over to the continental system just because it entered an economic pact. And it doesn’t have IDS.

“What do you mean by “bad patent” (or thoroughly bad patent) Paul?”

A “bad patent” is a patent that someone is suing microsoft or cisco for infringing, of course 😉

To me, a bad patent is one that shouldn’t have been granted due to 102, 103, or 112 issues. If it can’t be invalidated based upon one of those, it’s not a “bad” patent. It seems that some take the view that a broad patent is a “bad” patent.

Are there non practicing entities who buy up patents and sue large companies, as a business plan? Yes. However, patents are a property right. Moreover, if Large Company A sues Large Company B for infringing it’s patent (that it’s not “using”), how is that really any different? I think the patent “trolls” are an evil that we cannot avoid without eviscerating the patent system.

Moreover, it seems that some just don’t understand how important patents are to certain companies, particularly small and mid-sized companies. I’m currently prosecuting some mission-critical patents for small and mid sized companies where, if I can’t get them the patent, they may be hurting seriously. (too easy for a larger company to copy their product if no protection).

Above it is written “Drop IDS and IC. No other country has them”. But that’s not right, is it. Every country that runs English common law has equity, no? It’s just that most of Asia and all of mainland Europe runs something (civil law) that is NOT English common law, and England now belongs to Europe (Englishman Paul Cole, above, makes his usual wise contribution). But, hey, there’s more to the world than just Asia and old Europe. Don’t forget Australia. Things have come to a pretty pass when an American can suppose that the USA is the only place left on earth, where English common law still operates. You’re not completely alone, yet. Mind you, Australia did requide IDS for quite some time, but scrapped the idea recently. Wasn’t serving any useful purpose, the Australian Government decided.

“When you consider the windfall that results, compared to the remote chance of sanctions/imposition of attorney’s fees, I would expect that every accused infringer would assert the IC defense.”

Try this:

When you consider the windfall that results, compared to the remote chance of sanctions/imposition of attorney’s fees, I would expect that every patentee would sue or threaten to sue as many entities as it could afford to, regardless of how the patent was obtained.

Welcome to capitalism.

Drop IDSs and Inequitable Conduct. No other country has them.

What do you mean by “bad patent” (or thoroughly bad patent) Paul?

Aren’t 102, 103, 112 etc sufficient grounds to invalidate them?

The US judges I have met, or seen speaking at conferences, are wiser than many give them credit for. Often, it seems that inequitable conduct is simply a way of removing from the court’s docket a thoroughly bad patent and awarding attorneys fees within a system that has no other way of doing so. If you think the judges are being arbitrary or unreasonable, take some time to read the patent and study the trial record. Most often you will appreciate why they acted in the way that they did.

When I was studying chemistry, the concept of entropy was explained as flowing form the fact that a system would explore every state available to it. Likewise defendants plead every defence that they can, and the inequitable conduct defence is arguably over-used. But suggest to an audience of US patent lawyers that inequitable conduct and the large boxes of irrelevant documents finding their way to the USPTO should be abolished, and feel the reception you get. I know – I have tried it at a conference and before a federal judge as guest speaker, and the audience reaction was very hostile. The inequitable conduct defence is there because people in the US like having it in place. The rules of the game are not going to change any time soon.

Judge Rader also affirmed a district court determination of no inequitable conduct in the Eisai case:

Inequitable conduct in prosecuting a patent application before the United States Patent & Trademark Office may take the form of an affirmative misrepresentation of material fact, a failure to disclose material information, or the submission of false material information, but in every case this false or misleading material communication or failure to communicate must be coupled with an intent to deceive. Innogenetics, N.V. v. Abbott Labs., 512 F.3d 1363, 1378 (Fed. Cir. 2008). Materiality, defined as “what a reasonable examiner would have considered important in deciding whether to allow a patent application,” and intent are both questions of fact, and require proof by clear and convincing evidence. Id. To satisfy the “intent” prong for unenforceability, “the involved conduct, viewed in light of all the evidence, including evidence indicative of good faith, must indicate sufficient culpability to require a finding of intent to deceive.” Kingsdown Med. Consultants, Ltd. v. Hollister Inc., 863 F.2d 867, 876 (Fed. Cir. 1988) (en banc) (citing Norton v. Curtiss, 433 F.2d 779 (CCPA 1970)). Gross negligence is not sufficient. Id. This is a high bar.

See link to patentdocs.net

N.B.: Judge Moore wrote the Innogenetics opinion

Although I’m sure there are exceptional cases, generally speaking I think IC is an infringer’s wet dream. When you consider the windfall that results, compared to the remote chance of sanctions/imposition of attorney’s fees, I would expect that every accused infringer would assert the IC defense. It’s probably almost as routine as a criminal defense attorney making a motion for judgment of acquittal at the close of evidence. In fact, failure to do so is tantamount to a prima facie case of malpractice (and in the criminal realm, ineffective assistance of counsel).

* “Somehow, the EP examiner can find the best art, but the U.S. examiner needs his hand held.”

…and still doesn’t find the best art (or can’t/wont’ read it properly). *

The other day I wasted more than an hour trying to discuss a prior art ref with an Examiner. His command of English vocabulary was so poor that he honestly believed “maintain” to mean the same thing as “initiate.”

While I acknowledge that it makes prosecution difficult, I do not find it “trouble”…”that it allows even simple negligence (“should have known”) to shift the burden of persuasion on intent to the patent owner.”

If a person wishes to be granted a monopoly by the government, and create a corresponding deprivation of public good, *all* of the burden should be on him.

For those who don’t like to read, summary of the above:

In 1988, burden of proving inequitable conduct was on infringer. Over the next twenty years, the burden has shifted to the patentee. Today, the infringer simply need only call the patentee a cheater and the patentee has to spend enormous resources to prove they are not. Of course, in trying to prove you are not a cheater, you look like a cheater.

Judge Newman and Judge Rader are hip to this infringer scam and are trying to shift the inequitable conduct burden back to the infringer (OK, “alledged” infringer). Since inequitable conduct it is an easy way for a judge to get a patent case off their docket and it is easier to be on the safe side and rule against a potential cheater, the burden shift may not happen.

I think McKesson case from last summer is also a high-water mark for inequitable conduct for related cases scenarios. Note the Newman dissent there as well.

“Somehow, the EP examiner can find the best art, but the U.S. examiner needs his hand held.”

…and still doesn’t find the best art (or can’t/wont’ read it properly).

Amen to Prof. Janicke’s conclusion.

Why was it ever a good idea to require a lesser showing of intent to deceive when the omitted material was shown to be more material?

Let’s join the other 99% of the world, and quit requiring information disclosure statement submissions. Somehow, the EP examiner can find the best art, but the U.S. examiner needs his hand held.

Comments are closed.