Abraxis BioScience v. Navinta (Fed. Cir. 2011) (en Banc opinion) (original panel opinion)

The case centers on patents covering the anesthetic Naropin and Navinta’s attempt to begin manufacturing a generic version. Abraxis sued Navinta after that company filed its abbreviated new drug application (ANDA) with the Food & Drug Administration (FDA). See 35 U.S.C. §271(e)(2).

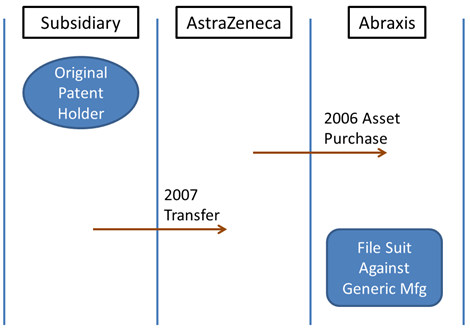

Problem of Ownership: In the original appeal, Judges Gajarsa and Linn found that the plaintiff, Abraxis, lacked standing because it did not own the patents in suit at the time that the complaint was filed. Although Abraxis had an asset assignment agreement from AstraZeneca with an effective date of June 2006, AstraZeneca had not actually received title from two of its subsidiaries by that date. Just before the lawsuit was filed, AstraZeneca received title to the patents from its subsidiaries and Abraxis argued that the 2006 agreement operated to automatically shift title to Abraxis. The chart below largely captures this (simplified) sequence of events.

The agreements spelled-out that New York state law should be the source of contract interpretation for these transfers. When applying New York law, the district court sided with Abraxis – holding that the circumstances in this case meant that the 2007 transfer should be deemed retroactive to 2006, nunc pro tunc.

The New York law may seem a bit strange to some, but the dispute between Judge O’Malley and the majority opinion is not about the interpretation of New York law. Rather, the questions is whether patent ownership should even be governed by New York law at all – as opposed to the federal rules of patent ownership and transfer that stem from the statutory guidance of 35 U.S.C. § 261 (both patents and applications are “assignable in law by an instrument in writing”). In several cases involving the interpretation of patent rights, the Federal Circuit has taken the opportunity to develop its own law. Examples of these include, DDB Techs., L.L.C. v. MLB Advanced Media, L.P., 517 F.3d 1284, 1290 (Fed. Cir. 2008); Speedplay, Inc. v. Bebop, Inc., 211 F.3d 1245, 1253 (Fed. Cir. 2000) (stating that while the ownership of patent rights is typically a question exclusively for state courts, the question of whether contractual language effects a present assignment of patent rights, or an agreement to assign rights in the future, is resolved by Federal Circuit law); and Bd. of Trs. of Leland Stanford Junior Univ. v. Roche Molecular Sys., Inc., 583 F.3d 832, 841-42 (Fed. Cir. 2009) (cert. granted Nov. 1, 2010). The court claimed jurisdiction over the assignment/contract questions in these cases because answer to the questions would determine the plaintiff’s standing to sue for patent infringement.

Here, Judge Gajarsa also found the interpretation of the purchase agreement to be an issue of Federal Law – writing that “[n]otwithstanding New York law, it is not possible to transfer an interest in a patent unless one owns the patents at the time of the transfer.”

In dissent, Judge O’Malley would have left the interpretation of the contract and property rights transfer as a matter of state law.

[B]y virtue of this decision, this court now requires the application of Federal Circuit contract law to transfers of existing patent rights, without regard for the state law jointly chosen by the contracting parties. The consequences of this decision are not slight. This creation of a new body of law to govern transfers of patent rights – one applicable in this Circuit only – will disrupt substantial expectations with respect to the ownership of existing patents and impose unnecessary burdens on future transfers thereof. Parties may now be barred from pursuing claims for infringement of patents they indisputably own under state law, and choice of law provisions in large-scale asset purchase agreements such as that at issue here will become meaningless where patents are involved.

Because this decision conflicts with Supreme Court precedent and needlessly destabilizes parties’ expectations, we should take the opportunity to correct this flawed precedent.

This decision is important for several reasons:

-

Now, any major or complex asset purchase or corporate reorganization must be reviewed by someone familiar with Federal Circuit Patent Transfer Law in order to ensure that the patent portion of the transfer is done in accordance with federal law.

-

It is unclear whether this Federal Circuit interpretation of the law applies only when the resolution is related to a standing issue. Namely, when judging a contract dispute would a state court be required to apply this law in their interpretation of the patent ownership rights or, alternatively, do the federal courts now have federal question jurisdiction over contract cases that require resolution of this type of contract language?

-

It is interesting that Judge O’Malley’s first patent opinion is a dissent to an en banc re-hearing that is joined by Judge Newman. Is this a sign to come for her tenure?

In response to the second bullet-point question posed above, the majority opinion narrowly limits the question (of federal common law) to whether an assignment is present. This opinion should not create any confusion over whether state or federal law applies to interpreting contracts with that language — although the Supreme Court (of the United States) may depending on how it rules in the pending Stanford v. Roche case!

Judge Newman’s dissent in the panel almost had me convinced. But she (and the district court) addressed the assignment clause of the June 28, 2006 Agreement, NOT the April 26, 2006 Agreement, which created the gap in title.

Nonetheless the opinions demonstrate quite clearly the need for Congress to weigh in on transferability of assignments and licenses to letters patent. The conflict between state and federal authority alone is enough to multiply the costs of any transactions or litigations of patents.

Why is that not part of this round of patent reform?

Spam.

Dennis – these spam messages are starting to get ridiculous. You might have to implement those really annoying captchas.

WCG, I am not so sure. How does inventorship get involved with issued patents?

In my opinion, the majority has confused ownership with inventorship (a matter of federal/patent law). Once the patent has been assigned, it becomes a matter of ownership of property. This case seems to impliedly create federal property law.

I must admit that when I read DDB Tech. v. MLB, I was angry. I thought then that the Federal Circuit was trying to find a way to hand it to DDB Tech. If you haven’t read that case, I urge you to do so. Not only is that case significant for its use of federal law to resolve a contract dispute, it is significant for it lack of use of a statute of limitations “defense.”

What had happened there is that a ex employee had obtained a patent, formed a company, and more than a decade later had sued MLB for patent infringement. MLB asserted that the employee’s company owned the patent by virtue of contract of present assignment. They won, or at least got a remand to see if the patent fell within the scope of the assignment agreement.

The problem with all of this was that the employee had informed the company that he was obtaining the patent, generally what it covered, and had received a waiver. So, the employee continued to invest in his patent and business and then, more than a decade later sued, only to find that MLB could assert that the employee did not own the patent, this, despite the fact that the company knew of the patent application, granted a waiver and had done nothing to assert an adverse interest for well more than the applicable SOL.

Something similar happened in Stanford v. Roche, but with the slight variance that the patent holder was suing the party having the alleged ownership by assignment and there was no prior notice and waiver.

Statute of limitations is also a state law defense to a contract claim. I don’t understand why it shouldn’t apply equally well to both an obligation to assign and to a present assignment. The breach occurs, in my view, when the obligation is breached by filing the patent application by the employee. There may be some tolling due to lack of notice, but certainly, if the employee does notify and receive a waiver, the period of time to sue begins.

So, if the employer sleeps on his rights and does not sue, it appears that the employee is still SOL, so to speak, because the Feds will now deny him standing, even decades later, by holding that the patent is owned by the former employer regardless of whether the employer’s claim is barred by the SOL.

I really do not think this is just. It is wrong and immoral on numbers of grounds. There is a reason we have SOLs and there is a reason we have “adverse possession.”

“Let’s hope not.”

mmmmm fluffy

The Supreme Court, unlike many lower courts, is almost always concerned about the broader consequences of its decisions, not just the unique facts of the case before it.

—————

BTW, here’s an interesting possible consequence of the outcome of this legal dispute to cogitate. If the Sup. Ct. says state law controls, could that not impact the legality of attorneys drafting patent assignment agreements if they are not members of the bar of the subject state, unless done under the supervision of someone who is?

It is interesting that Judge O’Malley’s first patent opinion is a dissent to an en banc re-hearing that is joined by Judge Newman. Is this a sign to come for her tenure?

Let’s hope not. Although I agree with the dissent in this case.

“Will there be some way that this latest Abraxis Fed. Cir. decision will be appropriately brought to the attention of the Sup. Ct. in the Stanford case? ”

Um, no.

Most (!) courts only hear the case that is actually before them.

The latest (Jan./Feb. 2011) ABA IPL “LANDSLIDE” magazine starting on p.24 has an extensive legal research article on inconsistencies and conflicts in Fed. Cir. cases with basic Sup. Ct. principles on the [normal, unless Federally essential] utilization of state law versus “federal common law”. Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Jr. University v. Roche Molecular Systems, Inc., 583 F.3d 832, 841 (Fed. Cir. 2009) is cited. However, this article was apparently written before cert was taken in that case.

Now we also have this new and relevant Fed. Cir. Abraxis decision on this same issue with Judge O’Malley, joined by Judge Newman, filed a 19-page dissenting opinion, arguing that the 3-judge panel created federal common law to govern assignments of existing patents in conflict with Supreme Court precedent restricting judicial preemption of state law and ignored New York state law when interpreting the contract. Amazingly, I found that the above new Fed. Cir. Abraxis decision mentions, once, their prior Stanford case, but without noting that the Supreme Court has taken cert on it! [Footnote 3 of the dissent does note the above “LANDSIDE” article.]

The Stanford case is now at the Supreme Court, as case No. 09-1159, with oral arguments expected in late April. However, it seems to be argued primarily on the basis of Bayh-Dole government rights that are impacted by the Fed. Cir. interpretation of the then Stanford employment agreement without regard to the California law which is discussed in the above “LANDSIDE” article?

Will there be some way that this latest Abraxis Fed. Cir. decision will be appropriately brought to the attention of the Sup. Ct. in the Stanford case? [The fundamental issue of whether or not the Fed. Cir. can apply its own views on contract law without regard to the law of the state in which the contract was executed on all patent assignments and employee invention agreements is obviously even more important than the Bayh-Dole issue.]

Comments are closed.