Guest post by Sarah Burstein, who will joining the faculty of University of Oklahoma College of Law this August. Her research focuses on design patents, an important piece in the smartphone wars. – Jason

Apple, Inc. v. Samsung Electronics Co., Ltd. (Fed. Cir. 2012) Download 12-1105

Panel: Bryson (author), O’Malley (concurring in part and dissenting in part), Prost

On May 14th, the Federal Circuit issued its first opinion in the world-wide, multi-front patent war between Apple and Samsung. In this opinion, the Federal Circuit considered the district court’s denial of Apple’s motion for a preliminary injunction based on infringement of three design patents and one utility patent, affirming in part and vacating in part. The opinion provides notable holdings in the areas of irreparable harm and nonobviousness.

In the motion, Apple argued that Samsung’s Galaxy S 4G and Infuse 4G smartphones infringed U.S. Des. Patent No. 618,677 (“the D’677 patent”) and U.S. Des. Patent No. 593,087 (“the D’087 patent”) and that Samsung’s Galaxy Tab 10.1 tablet computer infringed U.S. Des. Patent No. 504,889 (“the D’889 patent”). Apple also argued that all three of the devices—along with Samsung’s Droid Charge phones—infringed U.S. Patent No. 7,469,381 (“the ’381 patent”), which claims the iPad and iPhone “bounce” feature. The district court denied the motion based on, among other things, its findings that: (1) Samsung had raised substantial questions regarding the validity of the D’087 and D’889 patents; and (2) although the D’677 and ’381 patents were likely valid and infringed, Apple had failed to provide sufficient evidence on the issue of irreparable harm.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the denial of preliminary injunctive relief with respect to the D’677, D’087, and ’381 patents based on a lack of irreparable harm. The Federal Circuit concluded that the district court had not abused its discretion in finding no likelihood of irreparable harm with respect to the D’677 and ’381 patents. And although the Federal Circuit rejected the district court’s conclusion that the D’087 was likely anticipated, it still found no abuse of discretion in the denial of the preliminary injunction “[b]ecause the irreparable harm analysis is identical for both smartphone design patents.”

On the issue of irreparable harm, the Federal Circuit rejected Apple’s argument that the district court erred in requiring Apple to demonstrate a nexus between the claimed infringement and the alleged harm. According to the Federal Circuit: “If the patented feature does not drive the demand for the product, sales would be lost even if the offending feature were absent from the accused product. Thus, a likelihood of irreparable harm cannot be shown if sales would be lost regardless of the infringing conduct.” On appeal, Apple had argued that the district court had erred in rejecting Apple’s dilution theory of irreparable harm. The Federal Circuit disagreed, noting that “[t]he district court's opinion thus makes clear that it did not categorically reject Apple's ‘design erosion’ and ‘brand dilution’ theories, but instead rejected those theories for lack of evidence.” However, the Federal Circuit agreed with Apple that it “would have been improper” for the district court to completely reject “design dilution as a theory of irreparable harm.” The Federal Circuit did not explain why it “would have been improper” or provide any further explanation.

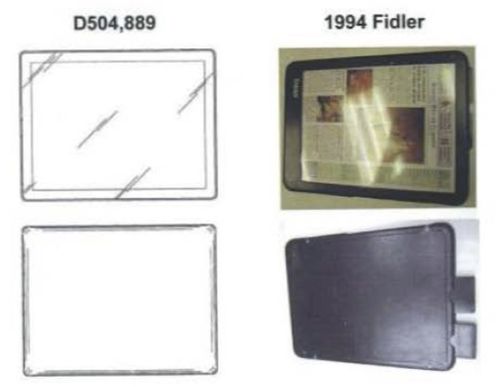

The Federal Circuit did, however, vacate the denial of preliminary injunctive relief with respect to the D’889 patent. The district court had found that the D’889 patent was likely obvious, using a 1994 tablet design (the “Fidler tablet”) as the primary reference. In the design patent context, any finding of obviousness must be supported by a primary reference—i.e., there must be “something in existence” that has “basically the same” appearance as the claimed design. If a primary reference is found, then the analysis proceeds. But if there is no primary reference, the inquiry ends—the design cannot be obvious. The Federal Circuit disagreed with the district court, holding that the Fidler tablet was not a proper primary reference. The Federal Circuit stated that “[a] side-by-side comparison of the two designs shows substantial differences in the overall visual appearance between the patented design and the Fidler reference,” pointing to the following illustration:

Without a primary reference, the district court’s finding that Apple was unlikely to succeed on the merits could not stand. And the district court had found that Apple had demonstrated a likelihood of irreparable injury with respect to the D’889 patent. However, because the district court had not made any findings on two of the preliminary injunction factors—the balance of harms and the public interest—the Federal Circuit remanded this portion of the case for further proceedings.

In her partial dissent, Judge O’Malley disagreed that the case should be remanded for further proceedings. According to Judge O’Malley, the district court’s discussion of these factors with respect to the other smartphone patents supported the entry of an injunction against the Galaxy Tab 10.1. Judge O’Malley also expressed concern that the remand would create undue delay, stating that “courts have an obligation to grant injunctive relief to protect against theft of property—including intellectual property—where the moving party has demonstrated that all of the predicates for that relief exist.”

Comment: The Federal Circuit’s conclusion regarding the Fidler tablet was surprising. Only a few years ago, a leading commentator observed that “[a]s a practical matter, [the requirement that the designs have ‘basically the same’ design characteristics] means that the primary . . . reference in a §103 design case needs to illustrate perhaps 75-80% of the patented design.” Perry J. Saidman, What Is the Point of the Point of Novelty Test for Design Patent Infringement?, 90 J. Pat. & Trademark Off. Soc’y 401, 419 (2008). Using that rule of thumb—or really, any ordinary meaning of the phrase “basically the same”—the Fidler tablet would easily qualify as a primary reference. Of course, that would not mean that the D’889 patent was obvious; indeed, there does not seem to be (at least from the public portion of the record) any persuasive evidence that an ordinary designer would have been motivated to modify the Fidler tablet in the manner shown in the D’889 patent. But this strict reading of the “basically the same” requirement may make it more difficult to prove obviousness in future design patent cases. And while it’s too early to declare a trend, it is worth noting that the Federal Circuit affirmed a rather strict reading of this requirement last year in Vanguard Identification Systems, Inc. v. Kappos (a case I discussed in a recent article).

The other especially striking portion of this opinion is the Federal Circuit’s unquestioning acceptance of Apple’s “design dilution” theory of irreparable harm. This sort of express equation of the harm caused by design patent infringement with the harm caused by trademark dilution is unprecedented in design patent case law (although not in the academic literature) and Apple’s theory deserves more attention and consideration than the Federal Circuit appears to have given it in this case.

Insightful commentary, from a leading quoter.

Lakshmielectro is an authorized dealer of GIVI Measure Products, Sew Eurodrive GMBH, Delta Tau (Switzerland), Weicon (Germany) Wire Stripping Tools and Machine Tool Retrofits with Fanuc/Siemens.

Thanks!

The Federal Circuit noted the following differences (slip op., pp. 28-29):

“First, the Fidler tablet is not symmetrical: The bottom edge is noticeably wider than the others. More impor-tantly, the frame of the Fidler tablet creates a very differ-ent impression from the “unframed” D’889 design. In the

Fidler tablet, the frame surrounding the screen contrasts sharply with the screen itself. The Fidler screen appears to sink into the frame, creating a “picture frame” effect and breaking the continuity between the frame and the screen embedded within it. The transparent glass-like front surface of the D’889 patent, however, covers essen-tially the entire front face of the patented design without any breaks or interruptions. As a result, the D’889 design creates the visual impression of an unbroken slab of glass extending from edge to edge on the front side of the tablet. The Fidler reference does not create such an impression.

There are other noticeable differences between the Fidler tablet and the D’889 patent that contribute to the distinct visual appearance of the two designs. Unlike the D’889 patent, the Fidler reference contains no thin bezel surrounding the edge of the front side. Additionally, one corner of the frame in the Fidler reference contains mul-tiple perforations. Also in contrast to the D’889 patent, the sides of the Fidler reference are neither smooth nor symmetrical; it has two card-like projections extending out from its top edge and an indentation in one of its sides. And the back of the Fidler reference also conveys a visual impression different from that of the D’889 design.”

All these patent drama is making me dizzy. The way I look at it, maybe this is just the way Apple wants to deal with the looming threat that is Samsung.

The man from the tower spins Newman incorrectly.

“Questions of law don’t have standards of proof, they have answers.” Yes, but that is what newman is saying. Quite the reverse of your next statement “If there is a standard of proof,” Newman’s point is that since obviousness is a question of law (and hence not fact with fact’s standards), the law’s correct conclusion does not matter which fact standard is in play (the Court’s more stringent or the loose Office one). Newman is saying that since the same issue has been concluded as a matter of law, even if the Office has a looser standard on facts feeding into that law, the law is still the law and does not depend on a standard of proof. In other words, the entire argument that the procedure in the Office bears on facts with a different standard falls away if the matter is a question of law.

What Newman seems to overlook however is that the law is not applied in a vacuum, but rather is applied to the facts as determined, and it is those determined facts that can (and here, do) differ.

Jerry below is correct.

Ben, Ned, is it of any interest to you, that in 1973 the Europeans wrote this into their European Patent Convention…..

“Article 25: Technical opinion. At the request of the competent national court hearing an infringement or revocation action, the European Patent Office shall be obliged, on payment of an appropriate fee, to give a technical opinion concerning the European patent which is the subject of the action. The Examining Division shall be responsible for issuing such opinions.”

From time to time, judges in patents courts around Europe do make use of it.

More recently, the UK legislator has also enabled the UK PTO to issue validity opinions, on request, for a modest fee. You can see from its transparent website that there is healthy demand, met with quick delivery of opinions, of which the courts take notice.

“In fact, the PTO proceeding has the advantage of both a lower standard of proof and of BRI. ”

A feature, not a bug.

“So, rather than reducing litigation costs, reexaminations are both undermining due process, raising the costs to the patent owner and fundamentally undermining the value of patents and therefor of our patent system.”

Again, a feature, not a bug.

Yep, maybe, and nope.

Since a judge has the liberty of calling its own experts, Kappos should a first step by proclaiming an open offer – in the course of the Court’s control – to provide its official view on validity instead of as a separate procedure.

It might be a rocky road, but it’s the right thing to do.

Perhaps in detail, but not in substance. There should be a way for the patent owner to involve the government in the lawsuit over validity in such a way that the government too is bound by the outcome the litigation. For example, if patent validity is under litigation, I think the government should automatically be required to become a named party whereby it could make arguments independently of the defendant, bring art independently of the defendant, but could not make the decision: that being the province of the judge and jury.

“Newman is wrong.”

In what she is saying, she is correct.

In what she is applying what she is saying, she is wrong.

Right argument for the wrong situation.

“ if the accused design is closer to the one that is registered than is the prior art, then a finding of infringement looms”

Looks like the same overall impression to me as Egyptian Goddess.

According to the IPKat, on Monday the Court of Appeal in London will hand down its Decision in the parallel proceedings in the UK. In Europe, there is no requirement for non-obviousness. Good so. How any court can hope to reconcile eye appeal with “obviousness” beats me.

So, instead, in the EU the design must be not only new but also be of “individual character”. Now that I can relate to. Infringements are those that engender the same “overall impression”. That too, I can grasp.

At its simplest, if the accused design is closer to the one that is registered than is the prior art, then a finding of infringement looms. Where would that test leave Samsung?

How will the London judges view Fidler? How much individual character does Apple exhibit over Fidler? Stand by.

I think the more interesting question is how the current test for design patent obviousness accords with KSR. Seems to defy common sense to say that FIdler could not possibly serve as a primary reference. The differences between Fidler and the claimed design seemed pretty small. Under the current test, it seems like small differences can make all the difference, but that comes at the expense of all the other common features, which doesn’t seem right. Seems to throw even moderate creativity out the window, too.

On the other hand, if a few minor differences can differentiate a claimed design from pretty close prior art, similarly minor differences should also differentiate the claimed design from the accused product to the same degree. Provided the test for infringement stays at least as narrow as obviousness seems to be, this is probably okay.

“appears the majority thought they were not the same”

Did you read the case? There is no way tha twhat you are saying is close to being true? Are you even a lawyer?

“Sure the art cited was quite the same, but is was the exact same issues adjudicated.”

However, it appears the majority thought they were not the same.

“This is the price of clear-and-convincing.”

I’m surprised that Ned hasn’t picked up on this. Rather than the price of clear-and-convincing, this is the price for far too easy and uncontrolled of a finding the SNQ standard is (was). THERE is where Newman should rail that a taking has been had, for the THERE is where the evidentiary difference and presumption of validity have been revoked in a shadow realm of a rubber-stamping let’s take a look at it again Office.

Presumption. There you had it. There you don’t.

“and it’s hardly the place of an activist judge to change that by legislating from the bench.”

…with a straight face from IANAE.

Seems rather unreal.

Q:Which judges would that be (that show some judges are listening to Newman)?

A:”The other two on the panel”

Have you bothered to read the panel decision? Obviously not, because the other two do not buy Newman’s position. At all.

Not sure where you make the jump to “tending to agree with her in principle,” as the issue was identical. Sure the art cited was quite the same, but is was the exact same issues adjudicated.

The other two on the panel who rested their holding not on it being right, but because of prior Federal Circuit precedent. They went out of their way to suggest that the PTO should not decide the same issue decided by the courts differently. They were convinced that the issues here were not overlapping, and that it appears was critical to their decision not to follow their prior panel decision concerning the very same patent and very same references.

“This is the price of clear-and-convincing”

Only an avowed anti-patent person like IANAE would put it like that. But what do you expect from someone who has professed his love of Infringer’s Rights, like he did at Mar 08, 2012 at 09:41 AM

link to patentlyo.com

The glare on the Fidler is different than the glare on D’889.

Would someone explain what the differences are between the D’889 design and the Fidler Tablet.

I don’t see much.

I don’t get it. Maybe this is why I don’t practice design patent law. The design patent and Fidler photo look exactly the same to me. What’s the difference?

“Congress is not required to have a patent system at all”

Someone needs to shine a light on IANAE. The question isn’t “is Congress required” – that’s a done deal, and no one is asking that question (except obfuscationists).

“because the litigation was not the infringer’s idea”

No, the infringer’s idea is to get away with the theft of IP scott free.

“What this opinion does show is that some judges are now listening to Newman”

Which judges would that be?

its implementation was and is flawed.

Clearly. But if we’re deciding cases based on what the state of the law currently is, Newman is wrong.

Congress is not required to have a patent system at all, much less an effective one. This is apparently the system that they want, and it’s hardly the place of an activist judge to change that by legislating from the bench.

Write your Congressmen. Tell them that a quarter of all US jobs hang in the balance. Never mind that it’s not true, there’s a study that says so.

IANAE,

Imagine then that a patent owner is subjected to serial reexaminations that burn up all of the patent life of his patent, wherein he is again and again forced to spend tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, per year, every year, defending his patent against the government assault. Is this justice? Is this a patent system. Is this guaranteeing the patent owner any term at all?

I mark, IANAE, that if you do not see just how the government, by its shear weight and power, can exhaust any private party forced into litigation with it, you have no sense of proportion. The cynical infringers know how to keep a patent owner tied up forever. They are not bound by any estoppel regime to disclose all the art they have to the PTO. They can dribble it out as necessary to invoke the next reexamination.

Whatever promise reexamination once held to improve the patent system, its implementation was and is flawed. We need finality, just as Newman states. We do not need two bites at an apple. We do not need endless harrassment of the patent owner. We need justice.

The whole concept that the patent owner must defend on two fronts at the same time is unfair and unjust to the patent owner.

I’m sure this will elicit a predictable response, but it’s unfair (and unjust!) to everybody else in the country that the patent owner be allowed to assert a patent in court before the PTO is done with it.

IANAE, Congress has already changed the law regarding Inter Partes Review. The accused infringer has a choice: DJ or PTO. He cannot do both.

Regarding ex parte, the Courts should not sit, in my view. They should enjoin the PTO from proceeding in any case where the court has jurisdiction. The whole concept that the patent owner must defend on two fronts at the same time is unfair and unjust to the patent owner.

rather than being a low cost ALTERNATIVE to litigation, ex parte reexaminations have become second bites at the same apple for accused infringers.

There is never an “alternative” to litigation for an “accused infringer”, because the litigation was not the infringer’s idea. I’m sure this comes as a complete surprise to Judge Newman.

The legislative intent to create two concurrent invalidation proceedings is certainly clearer than the legislative intent to impose a clear-and-convincing standard of proof for one of them.

Whose fault is it if judges sit when they’re asked to stay?

What the Baxter decisions shows is that rather than being a low cost ALTERNATIVE to litigation, ex parte reexaminations have become second bites at the same apple for accused infringers. In fact, the PTO proceeding has the advantage of both a lower standard of proof and of BRI.

So, rather than reducing litigation costs, reexaminations are both undermining due process, raising the costs to the patent owner and fundamentally undermining the value of patents and therefor of our patent system.

Well, now, a prior panel decision is relied upon by Hal to overrule the Supreme Court relied upon by Newman? I like that logic.

What this opinion does show is that some judges are now listening to Newman and are tending to agree with her in principle.

That theory is flawed, for obviousness is a question of law, and the PTO, like the court, is required to reach the correct conclusion on correct law.

More nonsense. Questions of law don’t have standards of proof, they have answers. If there is a standard of proof, there are questions of fact involved, whether the Federal Circuit is prepared to admit it or not.

IANAE, Newman's reply

"My colleagues justify the PTO’s authority to overrule judicial decisions on the argument that the standard of proof is different in the PTO than in the courts. That theory is flawed, for obviousness is a question of law, and the PTO, like the court, is required to reach the correct conclusion on correct law. Any distinction between judicial and agency procedures cannot authorize the agency to overrule a final judicial decision. Even if the Federal Circuit were believed to have erred in its prior decision, the mechanism for cor-recting an unjust decision is by judicial reopening, not by administrative disregard. See Christianson, 486 U.S. at 817 (“A court has the power to revisit prior decisions of its own or of a coordinate court in any circumstance, although as a rule courts should be loath to do so in the absence of ex-traordinary circumstances such as where the initial decision was clearly erroneous and would work a manifest injus-tice.”). This procedure did not occur in this case."

To quote Hal Wegner:

In fact, there is nothing new in Baxter, which is “Swanson déjà vu”:

“[The patentee] argues that th[e] reading of the statute [ ]allowing an executive agency to find patent claims invalid after an Article III court has upheld their validity[ ] violates the constitutionally mandated separation of powers, and therefore must be avoided. We disagree. The Supreme Court has repeatedly held that ‘Congress cannot vest review of the decisions of Article III courts in officials of the Executive Branch.’ *** [T]he court’s final judgment and the examiner’s rejection are not duplicative – they are differing proceedings with different evidentiary standards for validity. Accordingly, there is no Article III issue created when a reexamination considers the same issue of validity as a prior district court proceeding.” In re Swanson, 540 F.3d 1368, 1378-79 (Fed. Cir. 2008)(citations omitted).

I never said it was, THEY said that they wanted to make a court for these entities. Ya tard.

using the same presentations and arguments, even with a more lenient standard of proof, the PTO ideally should not arrive at a different conclusion.

Nonsense. There have to be cases where a different standard of proof makes a difference. Otherwise, why was i4i such a big deal that it had to go all the way to the Supreme Court? Why was there so much drama in the comments of this very blog about the mere possibility of i4i coming down the opposite way and how it would catastrophically weaken patent rights? Why was OJ acquitted on criminal charges but found liable in a civil proceeding? Because sometimes it’s easier to convince people a little than to convince them a lot.

This is the price of clear-and-convincing. Sometimes the PTO will disagree. Even on the same evidence, they’re being asked a different question.

Dennis will comment on this case soon, but until then, we have another blockbuster decided just yesterday by the Federal Circuit:

IN RE BAXTER INTERNATIONAL, INC.

link to cafc.uscourts.gov

An infringer presented the same evidence of invalidity to a district court and to the PTO in a parallel reexamination request, which request resulted in a re-examination. The District Court and the patent office came to opposite conclusions regarding validity, the PTO after considering the Federal Circuit opinion affirming the District Court’s holding that the claims were not invalid. On appeal from the patent office, the Federal Circuit affirmed the PTO’s determination that the same claims were unpatentable over the same references, again holding that the PTO was not bound by a final judgment of the District Court when considering the same patent, the same references, and based upon a re-examination requested by a party to the judgment of the District Court. (The majority, however, appeared to believe that the references presented to the patent office were different. In fact, they were not),

In the appeal from the District Court case, the Federal Circuit affirmed the district court holding that the claims are not invalid on the basis that the infringer had failed to produce any evidence regarding the corresponding structure of means plus function elements and whether this corresponding structure was in the prior art.

In the parallel re-examination, the examiner, in contrast determined that the corresponding structure was in the prior art. The patent owner appealed to the Board. While the appeal is pending, the Federal Circuit opinion in District Court appeal was decided. The board considered the Federal Circuit’s opinion, but held that it was not bound by that opinion due to the different standards of proof between the patent office in the district courts and because of “broadest reasonable interpretation” claim construction of the PTO. They upheld the examiner. On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed 2-1, finding that the corresponding structure (the structure that was the missing proof in the District Court case) was in the prior art.

In commentary, the majority said this about Judge Newman’s dissent:

“Lest it be feared that we are erroneously elevating a decision by the PTO over a decision by a federal district court, which decision has been affirmed by this court, the following additional comments must be made. When a party who has lost in a court proceeding challenging a patent, from which no additional appeal is possible, provokes a reexamination in the PTO, using the same presentations and arguments, even with a more lenient standard of proof, the PTO ideally should not arrive at a different conclusion.

“However, the fact is that Congress has provided for a reexamination system that permits challenges to patents by third parties, even those who have lost in prior judicial proceedings.”

Judge Newman dissented on the basis that Congress did not intend and could not have possibly provided that the patent office overturn final judgments of district courts. In doing so, she cited a host of Supreme Court cases the goes back to the Supreme Court case dating from 1792:

In Plaut v. Spendthrift Farm, Inc., 514 U.S. 211 (1995) the Court traced the finality of judicial rulings in relation to the executive branch to Hayburn’s Case, 2 U.S. (2 Dall.) 409 (1792), which “stands for the principle that Congress cannot vest review of the decisions of Article III courts in officials of the Executive Branch.” Plaut, 514 U.S. at 218. The Court explained:

The record of history shows that the Framers crafted this charter of the judicial department with an expressed understanding that it gives the Federal Judiciary the power, not merely to rule on cases, but to decide them, subject to review only by superior courts in the Article III hierarchy—with an understanding, in short, that “a judgment conclusively resolves the case” because “a ‘Judicial Power’ is one to render dispositive judgments.

Moreover, judge Newman made the point that the same references that formed the basis of the PTOs decision were before the District Court. The majority did not seem to understand this, suggesting that the PTO was relying on different references. Judge Newman pointed out that this was not in fact the case. The identical references were before both the PTO and the District Court.

“special small claims court specially for copyright or patent cases brought by micro/small-entities.”

Entity size is not related to claims size.

Logic FAIL.

I think you misunderstand, they’re trying to make a special small claims court specially for copyright or patent cases brought by micro/small-entities. This has nothing to do with the copyright claims against firms or the USPTO and certainly has nothing to do with Bernie Knight’s piece.

Hmmm,

Looks like that copyright coverage piece by Bernie Knight isn’t looking so impressive to the USPTO folks after all.

“Last Thursday (May 10, 2012), a roundtable of intellectual property experts convened at the George Washington University Law School. It was co-sponsored by the USPTO and the U.S. Copyright Office. The purpose of this roundtable meeting was to consider the possible introduction of small claims proceedings for patent and/or copyright claims.”

Tha Director

“A leading commentator”?

Without getting into it, the “perhaps 75-80% of the patented design” is without substantial merit, necessitating the qualifier “perhaps”.

The author does justice to this fact by essentially trivializing Perry’s attempt at quantification: “Using that rule of thumb—or really, any ordinary meaning of the phrase “basically the same”—the Fidler tablet would easily qualify as a primary reference.”

“The Federal Circuit’s conclusion regarding the Fidler tablet was surprising.”—only if Perry’s musing is considered to have any substantial merit…which it shouldn’t be.

On a blank slate, the CAFC’s finding on this issue is evidence that it shouldn’t be considered to have any substantial merit.

Perry is to be applauded, however, for having the courage to express his musings in the first place.

I look forward to either a defense, retraction, or modification thereof, by the “leading commentator”.

The Federal Circuit stated that “[a] side-by-side comparison of the two designs shows substantial differences in the overall visual appearance between the patented design and the Fidler reference,”

LOL.

Looks like a solid Rosen reference to me, but see Durling v. Spectrum.